When I look back at 2024, there were a lot of great games that people enjoyed but personally, I didn’t buy many new ones. Mostly I stuck to things to cover for this site and a few safe bets like the remake of Silent Hill 2 and Astro Bot late in the year. Once upon a time, I would make lists of all the new releases that were coming out and how I was going to fit them into my budget. Nowadays I’m indifferent to most big, AAA blockbusters, either because they’re of a playstyle that’s just not for me or I don’t vibe with the world that’s being sold. Mostly though it’s because I simply can’t afford those important day one new releases that help game makers stay afloat.

If this is one of your first time visiting this site, I’m a proud Canadian. Unfortunately, that pride comes with a cost when it comes to video games. Nintendo Switch software hovers around $91 after tax with PlayStation 5 or Xbox games coming in well over $100. According to GameStop Canada’s website, Alan Wake II‘s physical release is around the price of a Nintendo Switch game. Last fall, it was over $100 before tax.

What makes video games so expensive nowadays and why my budget doesn’t stretch as far as it once did are 2 very easy to answer questions. Titles that are big enough to warrant getting a physical release cost more to make for the former, and the latter is that billionaires, CEOs as well as the middle-manager under President Musk have pretty much made it such that everyone but the super rich will be struggling until the heat death of the planet. Beyond the larger sociopolitical reasons though, it’s the evolution of how video games are sold in 2025 and much of it has to do with the death of GameStop. I’ll elaborate.

There are some great people working at the few GameStop locations that still exist in my city, but frankly I like to spend what little disposable income I have at a local store called Gamesxchange or PNP Games for releases both new and old. As someone who grew up in a small town where the only place to buy games was at Walmart, the first time I set foot in a Microplay – a new mostly defunct proto-GameStop in Canada – or EB Games when it eventually arrived in my province in 2000 was like stepping through the pearly gates. Whereas I had only ever experienced a department store with a video game section, here were stores that had shelves with nothing on them but titles both new and old. The conversation around GameStop today for most is either “is that still a thing?” or “Good Riddance!” but it’s not a belief I share. I would like nothing more than for there to be a healthy GameStop or an alternative and those who think it’s death won’t change things aren’t seeing the bigger picture.

Digital games, ones that can be bought online and downloaded to your PC or console of choice, are an incredible convenience. During the heyday of the Nintendo 64, I would read about games in Nintendo Power magazine like Goemon’s Great Adventure but I was at the mercy of Walmart or the local rental stores to carry it. While rental stores are out of picture, digital sales allow you to buy software regardless of you’re geographical region provided you have an internet connection.

Digital distributions has also allowed independent creators to open and flourish when they would have never had that opportunity in the traditional retail market. BancyCo, a Canadian developer based out of Ontario, craft wonderful games, but the smaller titles they make would perhaps be harder to pitch to a publisher whose looking to make a packaged good for example. This is just not limited to indies either, as the rise of WiiWare, Xbox Live Arcade and PlayStation Network during the 7th console generation saw companies like Capcom and Konami resurrect classic titles at a lower price point or bring out unexpected things like Mega Man 9 or Bionic Commando Rearmed.

The myth surrounding digital game prices is that they were kept on par with physical prices as to not anger the stores that sell the necessary hardware to play them. As big box retailers like BestBuy shrink their physical media section and the number of GameStop’s decline, digital games still remain the same price despite the elimination of costs related to producing cases, inserts, discs and carts. That’s because that when platform holders and publishers don’t have to work to appease outside partners, those controlling the ecosystems can pretty much do whatever they want.

Take last fall as an example when Sony announced a remaster of the 7-year old Horizon: Zero Dawn for PlayStation 5 and PC. If you were in possession of either a digital or physical copy, you could upgrade to the newer version for $10. Given its age, Horizon: Zero Dawn was regularly on sale or deeply discounted on PSN until one day it wasn’t . Following the announcement of the remaster, Sony increased the price of original and months prior removed it from their PlayStation Hits catalog you could access with a subscription. If your console happened to have a disc drive, you can still hunt for a cheap used copy, but those all in on digital, or only play on PC, are cut off from this cost saving strategy. This is just one of the downsides of an all digital future.

Then there’s the fact that digital games cannot be easily resold or traded in for new ones, which is something that people on budgets used to their advantage to buy new games. Now, I will state upfront that I’m not championing GameStop’s practice of buying games for $2 and then selling them for $20, far from it. But to understand how this is hurting the industry, this business model, and how games were once bought and sold, must be briefly discussed.

Christmas for video game lovers is still, well, Christmas, but once upon a time 2nd Christmas used to be E3, or the Electronics Entertainment Expo. During the summer, publishers would show off their new offerings to the press and retailers. This would gauge interest in how many copies should be produced and sold to stores like GameStop and Target. Sometimes this forecasting model worked, but it was never foolproof. Anecdotally, I remember reading nothing but high praise for Prince of Perisa: The Sands of Time during the summer of 2003 and it would go on to launch in November of that year for full price. Before New Years, I secured a copy with Tom Clancy’s Splinter Cell for $29.99 which is great for me, the consumer, but not for Ubisoft’s bottom line.

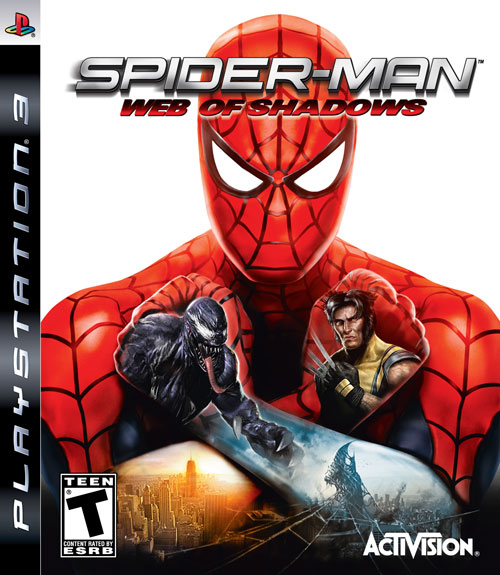

Retailers like GameStop thrived during the pre-digital, large physical print volume days. More copies in the wild meant stock was constantly being renewed without having to order and this kept prices down for those buying too. We’ve seen skyrocketing prices of retro and newer titles because they’re turning into antiques instead of products as the volume of physical goods is dropping or being horded by collectors. Fewer copies in circulation means even a common, licensed SNES title that was once $20 at a flea market is now pushing $100 or more for just a cartridge with no frills. Remember when something like Spider-Man: Web of Shadows would sit at the front of an EB Games with that impossible to peel off yellow sticker for $19.99? I’ve seen it selling for $100 in the past few months.

This just wasn’t for traded in titles, but also popular games that simply had too much stock. Every major platform holder used to have a “Greatest Hits” line, normally made up of software that was a year old or so. To clear out inventory, they would mark down popular games that made back their budget to $29.99 to make way for the new hotness. This was something I would take advantage of greatly as a poor university student as franchises like Jak, Sly and Ratchet would see their second installments plummet to make way for the third when the PS2 dominated the market.

Outside of the rise of digital, GameStop was equally hurt by local online markets like Facebook marketplace. Say you buy and finish a game you bought physically within a week. You can then turn around and sell it marked down from what GameStop is selling it for to recoup some of the costs. Sure, the retailer in this case doesn’t get that valuable trade-in, however the person who sold their game is likely to turn around and buy another new release. It’s a smaller profit margin, but it’s still profit. Trade-ins and resales are something you largely can’t do with digital only games, and without this, it means that players are less likely to take risks on games outside of established franchises or move to the free-to-play ecosystem.

This is actually what major stakeholders want. They don’t want to have to support multiple studios, gamble on pitches for new intellectual properties or have a diverse portfolio of every genre imaginable. Ever since the success of Fortnite, pretty much every publisher or venture capitalist have been trying to make their own version of that. One game that traps millions of players for years of their life who will spend copious amounts of money in that ecosystem. There’s no searching for the next big thing or the desire for artistic story telling, they just want a money producing treadmill.

This, however, is unsustainable due to the laws of well, physics. There’s only so many hours in the day, and sure, younger players with fewer responsibilities might be able to juggle multiple ongoing games but most adults can barely find a hour or two a day to relax with their device of choice. You don’t have to look far for proof either. Today it was announced that Spectre Divide, a free-to-start shooter that launched in September is closing down and taking its creator, Mountaintop Studios with it. I mean no disrespect to the people at Mountaintop, especially considering that many have to now look for new jobs, but I didn’t even hear about Spectre Divide until today. Discoverability is an issue for another day, but keeping momentum is far harder than building it.

When the barrier to entry is $0, it’s easy to try new things, but keeping a player base alive takes massive amounts of capital to keep pumping out new content and competing not just with other games, but everything else that’s fighting for your attention. I turned 40 last May, and I already find myself doing the “back in my day” shtick far too much. Not even 2 decades ago though, there was a lot of entertainment, but it was concentrated in a few places. Between streaming services, video games, Twitch, YouTube and countless other distractions, the ongoing war is for every second you have free time throughout a day.

I graduated from university with a Bachelor of Business Administration degree in 2007, but I’ve never considered myself a business savvy person. I limped across the finish line and my brain has been fighting a losing battle with remembering microeconomic theories and the differences between the multiples versions of Captain America and the Avengers. That’s a roundabout way to saying I don’t have a solution that will magically make everything like it was when people stood in lines for midnight launches and didn’t need to get a second job to afford games. All I know is that unless you’re a professional influencer whose job it is to cover shiny new things, you’re buying fewer games at launch and are waiting for sales instead. That is if you’re not already committed to one live-service game or replaying the classics to remember a simpler time when even those working minimum wage jobs could build a respectable software library.

Everyday I feel my interest in interactive entertainment slipping because the investment of both time and money is simply too great.